Not Bowling Alone: How the Holiday Bowl in Crenshaw Became an Integrated Leisure Space

By Ryan Reft | August 22, 2013 | LINK

In May 2000, the New York Times reported the upcoming demolition of the Crenshaw District’s Holiday Bowl. Built by Japanese American investors in 1958, just as Crenshaw and neighboring Leimart Park were reemerging as one of the city’s most diverse neighborhoods, the bowling alley served as an integrated leisure space where African, Mexican, and Asian Americans could interact. “It’s like a United Nations in there,” longtime employee Jacqueline Sowell told writer Don Terry. ”Our employees are Hispanic, white, black, Japanese, Thai, Filipino. I’ve served grits to as many Japanese customers as I do black. We’ve learned from each other and given to each other. It’s much more than just a bowling alley. It’s a community resource.”

Even amid the traumatic 1992 riots, numerous patrons, including Rodney G. King, sat outside the alley protecting it from looters telling anyone who approached “the bowl was ‘our place’.”

Obviously the importance of these spaces lay in fostering community, social awareness and political activism, but they also encourage us to think about how we define ourselves. In his own research, UC San Diego History Professor Danny Widener has excavated the importance of understanding the kind of interwar Afro-Asian, and by extension Jewish-Mexican American, alliances like those of earlier Watts and Boyle Heights iterations. Such alliances tell us as much about ourselves as others.

“Successive populations of immigrants from Asia played a fundamental role in the development of black understandings of life ‘out west,'” argues Widener.1 Indeed, patrons at Holiday Bowl, and by extension their peers — whether Jewish, Latino, or European — in the East and Southside neighborhoods understood themselves and the city through these prisms. Others have pointed to the Holiday Bowl as a recent example of long historical truth: black-Asian alliances are not new, nor are multicultural L.A. neighborhoods, but rather each rests on a deep historical foundation of cultural exchange that includes religion, personas, and lifestyles. “The Holiday Bowl allowed fealty between people of color to grow,” Vijay Prishad argued in his 2001 work, “Everybody was Kung Fu Fighting: Afro-Asian Connections and the Myth of Cultural Purity.”2

With L.A.’s growing prominence as a “global city,” and last year’s twentieth anniversary of the 1992 riots, which at the time revealed violent fissures between Korean and African Americans, it is timely to acknowledge past multiracial alliances and neighborhoods and the ways in which economic shifts, political decisions, and housing policies impacted these communities.

Soothing Trauma

In Nina Revoyr’s 2003 novel “Southland” Jackie Yishida goes on a quest to crack an unsolved murder while also investigating her own grandfather’s history in Crenshaw. The narrative crackles with black-Asian relationships, and within the larger story the Holiday Bowl, renamed Family Bowl, provides a key setting for her investigation. For her grandfather’s friend Frank Kenji, a WWII veteran and former Japanese internee, the Holiday Bowl salved deep psychological wounds. While on a brief leave from the military Kenji returns to witness the birth of his child, only to instead helplessly observe the death of both his newborn and wife at the hands of a racist, drunk, government doctor. A series of tragedies befalls Kenji and his loved ones. Though it hardly makes up for his family’s hardship, eventually Kenji discovers the healing power of bowling.

And then one afternoon outside of Frank’s store, Jesus came up to him again, dressed in normal white robes this time. He looked at Kenji and pointed over toward Crenshaw Boulevard. “You must bowl, my son,” He said. “Fill your hands with the nourishing weight of sport.3

Granted, Kenji’s reliability as a narrator might be in doubt, but no such reservations exist when considering the Holiday Bowl’s importance in mediating conflict, soothing trauma, and encouraging integration. In its initial years, the bowling alley served a predominantly Japanese American clientele and had been purposely constructed to return a sense of normalcy to the lives of thousands of citizens unfairly interned by the federal government. Four local Japanese American businessmen spearheaded efforts to build the alley: Harry Oshiro, Hanko Okado, Paul Uyemura, and Harley Kusumoto. The four men sold shares of the business in the local community to finance construction.

In Crenshaw and parts of Leimert Park, Japanese American faces and culture had begun to leave their mark on the area. “I used to drive to work along Exposition Boulevard and I’d see these homes with these beautiful [Japanese] gardens,” longtime Holiday Bowl coffee shop patron and local high school teacher Barbara Fuller told the founder of the Studio for Southern California History, Sharon Sekhon, and others who were part of the Holiday Bowl History Project in 2004. Located on Crenshaw Boulevard between Exposition Boulevard and Rodeo Road, the Holiday Bowl sat west of the fading local demarcation line for segregation — Arlington Avenue.

Though Japanese internment during WWII disrupted local patterns of diversity, Crenshaw existed as multiethnic community as early as the 1920s. Admittedly however, with the influx of greater numbers of African Americans from the Great Migration, increased attention to segregation had limited housing options for non-whites, such that up until the 1950s fewer opportunities for open housing existed.

Bowler Tony Nicholas’ own family bought a home in the 1940s, east of Arlington Avenue, at Van Ness and Exposition. At the time, “unwritten law” dictated that minorities could not settle west of Arlington Avenue, noted Nicholas. However, by the 1950s, his family had bought a home on Crenshaw between Adams and Washington, joining other black, Chinese, Japanese, and white homeowners in the area. For black Angelenoes, Leimert Park, Crenshaw, and West Adams offered new and better housing opportunities, especially as South Central’s population bulged. Leimert Park’s African American population demonstrated a solidly middle class orientation, as professionals made up 17 percent of employed black male residents and 19 percent of their female counterparts. With city wide averages of professional employment equaling 8 percent and 9 percent for black men and women respectively, Leimert Park and Crenshaw proved critical for L.A.’s African American middle and working class families.4

Bowler Tony Nicholas’ own family bought a home in the 1940s, east of Arlington Avenue, at Van Ness and Exposition. At the time, “unwritten law” dictated that minorities could not settle west of Arlington Avenue, noted Nicholas. However, by the 1950s, his family had bought a home on Crenshaw between Adams and Washington, joining other black, Chinese, Japanese, and white homeowners in the area. For black Angelenoes, Leimert Park, Crenshaw, and West Adams offered new and better housing opportunities, especially as South Central’s population bulged. Leimert Park’s African American population demonstrated a solidly middle class orientation, as professionals made up 17 percent of employed black male residents and 19 percent of their female counterparts. With city wide averages of professional employment equaling 8 percent and 9 percent for black men and women respectively, Leimert Park and Crenshaw proved critical for L.A.’s African American middle and working class families.4

While much of the city remained segregated, Fuller recalled, Crenshaw and Leimert Park weren’t — and “that’s what made [them] exciting.” Longtime resident and bowler Ken Hamamura agreed, noting that Dorsey High School on Exposition divided neatly along thirds: one third African American, one third Asian American — predominantly Japanese and Chinese Americans — and one third white. As the neighborhood grew more multiracial so too did the bowling.

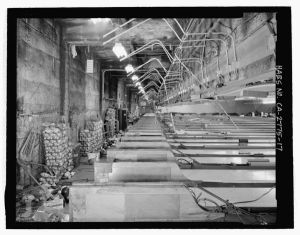

With its modern technology, the Holiday Bowl provided a better playing experience than most other local bowling alleys, and the competition featured numerous talented bowlers. “Holiday Bowl had the capacity to attract a lot of the better bowlers in the area,” remembers Arthur Sutton, recalling his days at the alley. “And if you want to be the best you have to compete against the best. And I loved that competition.”

The visual flair of the bowlers and their teams spoke to the diversity and enthusiasm at the heart of the Holiday Bowl enterprise. “Different groups would come at different times, and it was almost like looking at Bower ware in action. You know, Bower ware being all colorful, all these shirts were different colors — turquoise and black with yellow writing on it,” noted coffee shop patron Renee Gunther.

Early on many of the bowling teams consisted of local Japanese farmers, grocers, and merchants, all of whom competed in divisions that suited their profession: the Gardener’s League, the Produce League, and the Floral League, to name a few. When the area began absorbing greater numbers of African Americans, like the Nicholas family, the teams changed as well. “[M]y team has one black, one Italian, another Japanense, and Korean Sponsor,” Floral League member Dorothy Tanabe told the Los Angeles Times.5

Everyone Eats

While bowling stood at the heart of the Holiday Bowl, its coffee shop held an equal position of importance. Open 24 hours, the coffee shop’s clientele belied the local area’s diversity. Moreover, beyond race, it demonstrated the variety of interests, pastimes and lifestyles of the community. Cindy Akiyama’s mom waitressed at the coffee shop for years and Cindy frequently accompanied her mother, Clara Harris, to work. With Harris manning the graveyard shift, Cindy observed the bowling alley’s ability to serve the local community. From 12 a.m. to 8 a.m., one could witness very different and distinct crowds patronizing the alley and coffee shop. Late evening brought the league players consisting mostly of working and middle class folks. At 2:30 a.m. the bar crowd came in and, as one patron noted, seating became “standing room only”. By 5 a.m. workers on their way to their jobs popped in for a coffee and a danish. Crenshaw locals took meetings, went on dates, and socialized in the coffee shop. “It was a comfort zone right there in the community,” La Verne Hughes recalled.

What about the eats? “Chinese, food, Japanese food, American food,” Akiyama attested; “A wonderful eclectic menu,” noted Fuller. Rice was popular — rice with gravy, rice and chili — “I’d ask for a bowl of rice with whatever I was eating,” admitted Gunther. Local journalist Peter Y. Hong reflected in 1996 that one could one enjoy “eggs with either Chinese char siu pork or Louisiana hot links and rice. If it’s not, it’s probably the only place where you can eat like that and bowl.”

If in recent years writers have turned to sport for philosophical and sociological meaning, food has also enjoyed increased attention and scrutiny. Few cultural traditions overlap like the experience of sitting down for a meal; every culture has its own take, but everyone eats. In this context, the Holiday Bowl coffee shop provided the perfect intersection of sport and food, two of the most prominent means by which to bridge social interactions. Tony Nicholas remembers the sushi bar where one could observe Asian, Latinos, and African Americans eating and commiserating. “It’s where I had my first sushi,” he happily confessed in 2004. L.A. Novelist Nina Revoyr holds similar memories. Upon her first visit she knew the Holiday Bowl had a special quality. “Elderly black people were eating with elderly Japanese people, arguing about the Dodgers and telling stories about the things they had done in their youth,” she told interviewers in 2005.6

Fostering Community

The Holiday Bowl also took care to engage the community. In the 1960s it held fundraisers for sickle cell anemia and cancer research, and in the 1990s it worked with the Martin Luther King Jr. Therapeutic Center, an organization dedicated to helping autistic children. “They really rolled out the red carpet for us,” Kennic Ferguson of the MLK Center noted. For families, the Holiday Bowl provided a nursery so that little ones too young to enjoy the alley could play while their parents and siblings could bowl.

The kind of alliances created by the Holiday Bowl extended to the larger Crenshaw and Leimert Park community as organizations arose to encourage cooperation and unity. For example, founded in 1964 prior to the Watts riots, the Crenshaw Neighbors Association (CN), consisting of residents from both Crenshaw and Leimert Park, dedicated itself to the neighborhood by working to prevent white flight. Though predominantly African American, CN maintained a multiracial membership and eschewed black nationalism or militancy. In its quarterly magazine, The Integrator, the organization took aim at both “bigots” and “‘militant liberals.'” The former were little more than prejudiced reactionaries unable to adjust to changing times, while the latter’s use of civil disobedience “scare[d] the daylights out of probable candidates for integration.”7

Along with its magazine, CN conducted home tours and secured its own brokerage license to facilitate its role in local housing issues. In 1966, Crenshaw Neighbors, along with other like minded coalitions, formed the Council of Integrated Neighborhoods (COIN), focused on maintaining “open housing throughout the county and dissolution of the solid ghetto with its built-in tension, hatreds and property decay.” Whatever the pros and cons of its centrist approach, Crenshaw Neighbors continued to operate into the 21st century.

Yet, while the Holiday Bowl undoubtedly went out of its way to foster community, it remained subject to the economic and political winds around it. When the Watts Riots (or Rebellion depending on one’s point of view) erupted in 1965, things changed. Damage from the riots left the area economically handicapped and, as in Boyle Heights where a once diverse community became uniformly Mexican and Mexican American, Crenshaw grew nearly exclusively African American. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, white flight and the disappearance of factory work — Goodyear, Firestone, and Bethlehem Steel moved jobs overseas — the neighborhood lost racial and class diversity. As Crenshaw bowler Sam Jones pointed out, it could be plainly seen at the alley as fewer and fewer blue-collar players showed up.

Predictably, with 1970s economic decline and 1980s gang and crime epidemics, the night crowd grew rougher. On at least one occasion, bullets came through the diner’s window and more than a few patrons suffered robbery — and worse. Despite being unable to bowl anymore due to a violent robbery that occurred in the parking lot in 1986, George Furukawa continued to drop by the alley and restaurant for the occasional beer and cigarette. In the late 1980s the coffee shop’s graveyard shift was ended when gangs took over the parking lot in the evenings. Security guards hired in the 1990s helped to diminish such threats.

Even in decline, the community held tightly to institution. In fact, with rising numbers of Mexican Americans and the demographic decline of African and Japanese Americans in the Crenshaw area, the Holiday Bowl meant even more to aging longtime residents. When the 1992 L.A. riots burst, local patrons arrived at the Bowl to ensure its protection. “People [were] standing in front of the bowl while other buildings were being burnt around [it] … They were protecting it,” Nicholas recalled. “These were patrons … They were willing to risk harm to save this facility.”

Afterwards the Holiday Bowl continued to function but, as one regular noted, things weren’t the same. “The blustery waitress going table to table, dishes clattering, people eating, it just wasn’t happening anymore.”

Cultural Preservation

In 2000 the Holiday Bowl was sold and scheduled for demolition. Community members put up a staunch resistance, forming the Coalition to Save the Holiday Bowl. The coalition argued that the Holiday Bowl’s architecture stands as a prime example of Los Angeles’ idiosyncratic Googie style. The coalition also noted the cultural capital sewn into the building, notably its importance to the local Japanese American community reconstructing their lives after internment, and its role as an interracial recreation center suturing community bonds. In an era of crime in an area struggling with violence, the Holiday Bowl provided a peaceful space amid urban decline, the coalition asserted. In the end, the Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Commission and City Council decided in favor of partial preservation.8

In 2003 the building was demolished, leaving only the coffee shop and the alley’s neon signage. By 2006 developers had erected a Coliseum Center strip mall on the property, and a Walgreen drug store now sits where Crenshaw’s bowlers once plied their trade. The coffee shop façade remains as part of an Urban Coffee Starbucks. Whatever one thinks of the heritage commission’s decision, the Holiday’s Bowl’s disappearance exacted a cost. “It was almost like losing your family home,” Arthur Sutton lamented. “I don’t even like to go past there now, it stirs too many memories and that’s a part of my life that won’t be repeated.”

Indeed, partial preservation resulted in the loss of the building’s immaterial characteristics, notes Los Angeles architectural historian and preservationist Kathryn Horak. Interracial friendship, multiethnic interaction, and community atmosphere simply don’t rival the power of L.A. real estate interests. The question Horak correctly asks, is how do we establish a means to evaluate and broadcast “intangible cultural significance” to city officials and others; how can we ensure history and community do not get washed away by urban renewal and economic development?9

Thirty years ago in 1983 the United States Department of the Interior published a study that advocated for a reliable national system of cultural conservation. As Horak points out, the demolition of Holiday Bowl in 2003 occurred twenty years after the report, demonstrating that protecting valuable local cultural commodities remains a real problem in the face of urban reinvestment and economic development.

For decades the Holiday Bowl anchored the local Crenshaw neighborhood, providing constancy and community. Lifetime bowler Joe Yumagawa summed it up neatly. When he visited other bowling alleys, no matter how nice, “I’d feel like a stranger,” he confessed. The Holiday Bowl, however, “to me it just felt like home.” As nice as Walgreens and Starbucks might be, a home, they do not make, and memories they do not house.

1 Danny Widener, “‘Perhaps the Japanese are to be Thanked?’: Asian, Asian Americans, and the Construction of Black California,” in Positions, 11:1 (Spring 2003), pg 136.

2 Vijay Prishad, Everybody was Kung Fu Fighting: Afro-Asian Connections and the Myth of Cultural Purity, (Boston: Beacon Press, 2001), pg. 119.

3 Nina Revoyr. Southland. (New York: Akashic Books, 2004) pgs. 156-157

4 Josh Sides, L.A. City Limits: African American Los Angeles from the Great Depression to the Present, (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2003), pg. 122.

5 Vijay Prishad, Everybody was Kung Fu Fighting, pg 119.

6 Kathryn Horak, “Holiday Bowl and the Problem of Intangible Cultural Significance”, MA Thesis, USC , 2006.

7 Josh Sides, L.A. City Limits: African American Los Angeles from the Great Depression to the Present, (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2003), pgs. 191-192.

8 Kathryn Horak, “Holiday Bowl and the Problem of Intangible Cultural Significance”, pgs. 1-4

9 Ibid, pgs. 3-4.